THE FOREST

When the present Tionesta tract was acquired in 1936, old-growth hemlock stands predominated. Hardwoods, principally sugar maple and beech, were dominant on the remain- ing area. Most of the hardwood stands-particularly in the Scenic Area-were younger, contained much smaller trees, and generally occurred on the old windthrow areas (fig. 8). The forest type acreages shown in table 1 are the best estimates available.

Estimates of the forest types in the Scenic Area are based on 1936 cruise

data. At that time, black cherry types were not recognized, but it is

likely that such types were present then as they are now. Forest

type acreages in the Research Natural Area are based on a survey of the hardwood

forest types completed in 1975. Figure 9 shows the approximate boundaries

of the hemlock stands and the hardwood stands as sketched from old maps, aerial

photographs, and the Natural Area survey.

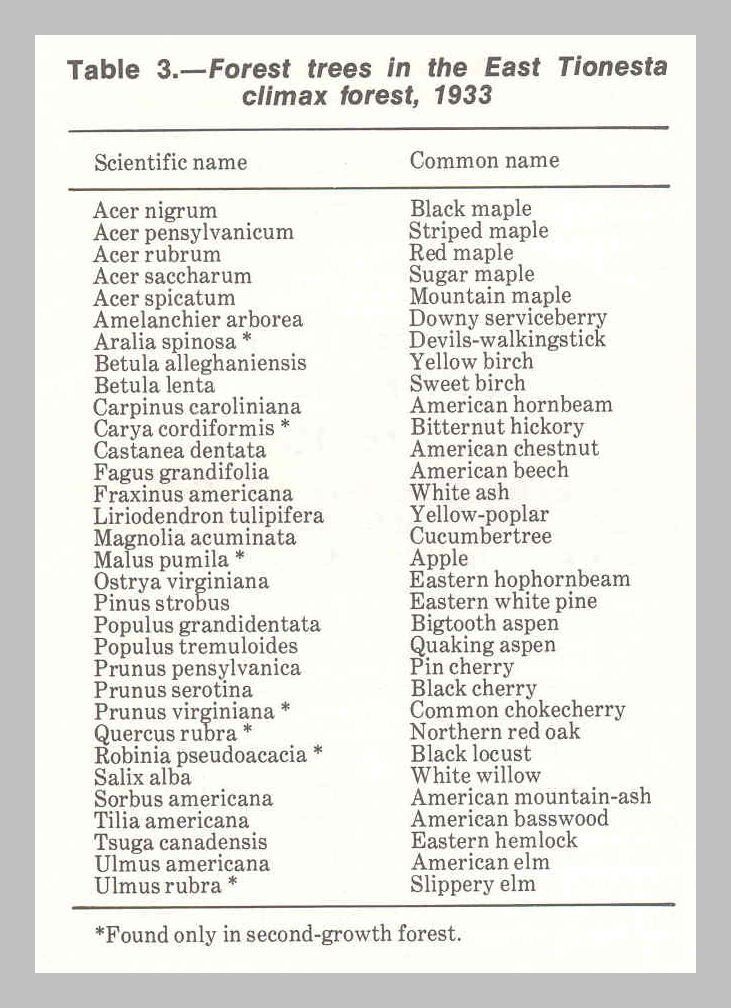

Surveys were made in 1930 and 1933 of the plant and

animal life in a 14,000-acre tract of climax forest extending from the valley of

the East Branch of Tionesta Creek south to and including the present Tionesta

Scenic and Research Natural Areas. Some small areas of second-growth

forest along the edges of the climax forest were also included. All the

climax forests outside the Tionesta Areas have since been cut.

At the time of these surveys, hemlock and beech ranked first

and second in frequency in the dominant tree cover-trees at least 70 feet

tall-on the plateau and slopes. Hemlock was the most common species along

Cherry Run and both branches of Fork Run. Other tree species varied

according to topographic position (table 2). Species such as oak, white

pine, and chestnut were of minor importance and, when present, were most likely

to be found on the warmer and drier south-facing slopes. This topographic

distribution is about the same today.

It is not known how many of the plants and animals listed

here can be found in the remaining climax forest; but some, such as black maple

and ostrich fern, are characteristic of larger valley bottoms and must have

occurred only along the East Branch. Neither white pine nor red oak have

ever been reported in the Tionesta Areas.

Figure 8.-Second-growth stands of sugar maple, red maple, and beech have developed in old windthrow areas. If left undisturbed for many years such stands may revert to a hemlock-beech climax forest.

Species observed in second-growth stands are included here because such

stands existed in the Tionesta tract in 1933 and there may be some overlapping

of species between the climax and second-growth forests. Species reported

in second-growth stands are marked in the following lists of flora and fauna.

In the surveys, 32 tree species were recorded (table 3).

A tree is defined as a woody plant having one erect perennial stem or trunk at

least 3 inches in diameter at breast height (4.5 feet), a more or less

definitely formed crown of foliage, and a height of at least 12 feet.

Page 9

Figure 9.- The shaded areas show the locations of the hardwood stands.

The remaining area is in the hemlock-beech forest type.

The principal species found were hemlock and beech.

The average basal area per acre was about 140 square feet. The basal area

of a tree is the area of a cross-section of a stem generally measured at breast

height, and includes bark. Basal area per acre is the sum of basal areas

of all the trees on the acre.

Hemlock was the dominant species in the 10-inch and larger

diameter classes; beech dominated in the 4- to 9-inch classes (table 4).

Sugar maple ranked second to beech in both abundance and frequency in trees less

than 30 feet in height. Other species were of minor importance in all size

classes.

Some acres were estimated to have as much as 50,000 board

feet of sawtimber. However, the average board-foot volume per acre for the

Tionesta Areas was estimated to be 15,000 board feet. Nearly three-fourths

of this was hemlock.

Tree heights up to 125 feet were recorded. And many

trees exceeded a diameter of 30 inches (fig. 10). The largest trees

included a 53-

Page 10

inch hemlock, a 50-inch red maple, a 48-inch yellow-poplar, and a 40-inch

black cherry. Hemlocks up to 560 years of age and a black cherry 258 years

old have been recorded in the parts of the climax forest that have since been

cut.

Twenty-seven shrub species have been recorded in the virgin

forest (table 5). A shrub is con-

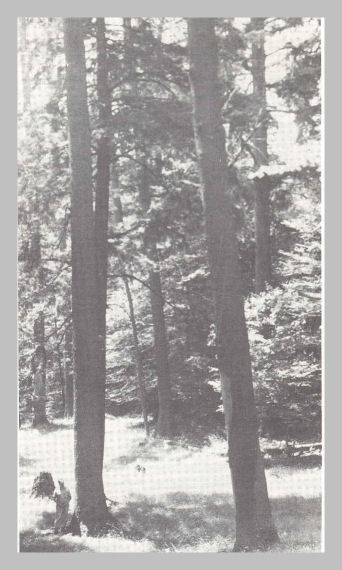

Figure 10.- The large tree on the left is a 35- inch black cherry tree. It is about 110 feet tall and about 140 years old. The large tree on the right is a hemlock of about the same size that died from natural causes.

sidered a woody perennial plant differing from a perennial herb in its

persistent and woody stem, and less definitely from a tree in its lower stature

and general absence of a well-defined main stem. Other understory

vegetation includes 4 club-mosses, 24 ferns, and 66 herbaceous plants. Of

these, hobblebush, maple- leaved viburnum, spinulose wood-fern, and shining

club-moss were the most common.

More than 60 species of birds were observed during the 1933

survey; probably all were nesting species. Included were predators (hawks

Page 11

and owls), water-loving birds (herons and: kingfishers), woodpeckers,

warblers, and song birds.

A total of 29 mammals were observed, ranging in size from

shrews and mice to black bear. Abundant species included chipmunks,

porcupines, and deer. Less common were such animals as mink, weasel, fox,

raccoon, squirrel, beaver, muskrat, and opossum. Black bears and bobcats

were rare.

Fifteen species of fish were observed, but most were found

only in the warmer waters of the main streams. The colder headwaters in

the tract contained only native brook trout.

Of the 13 amphibians recorded, salamanders were the most

common. Reptiles other than the common garter snake were rare.

In general, the trees, shrubs, herbs, mammals, and

reptiles observed were those species more common to a northerly climate.

Composite lists of all the species recorded in the virgin

hemlock-beech forest of the East Branch of Tionesta Creek in 1930 and 1933 are

given at the end of this report. However, since the forest is constantly

changing and different environments are created, some species may vanish while

the populations of others rise or fall in company with the changing habitats.

Other species may appear or disappear seasonally or with long-term climatic

changes. These are some of the reasons why the lists of observed species

can be only a guide to what might be present today.

Page 12